Ugandans under the age of 35 – and that is more than three-quarters of the population – have only known one president.

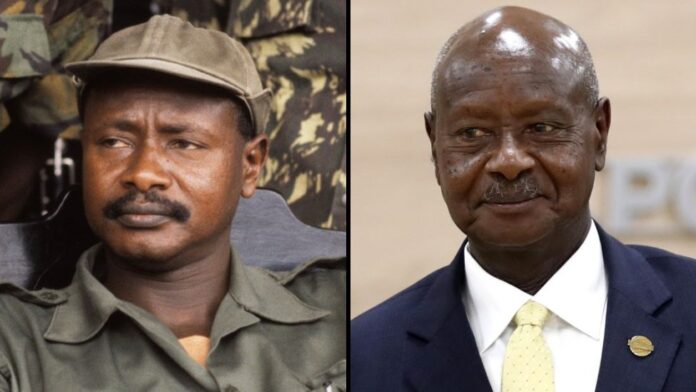

Yoweri Museveni, who came to power on the back of an armed uprising in 1986, has defied the political laws of gravity which have felled other long-serving leaders in the region.

The 76-year-old’s time at the top has been accompanied by a long period of peace and big developmental changes for which many are grateful. But he has managed to maintain his grip on power through a mixture of encouraging a personality cult, employing patronage, compromising independent institutions and sidelining opponents.

During the last election five years ago when he addressed the issue of him stepping down, he asked: “How can I go out of a banana plantation I have planted that has started bearing fruits?”

For this revolutionary the harvest is still not over.

My introduction to the president came in the 1990s in the form of a school play in which the turbulence of the Milton Obote and Idi Amin years was acted out.

The piece climaxed on 26 January 1986, with Mr Museveni’s National Resistance Army liberating the country, bringing an end to wars and senseless killings.

It is this image of the man as liberator and peace-bringer that many Ugandans have been raised on, and are reminded of at every opportunity.

Presidential press-ups

He is also a fatherly and grandfatherly figure.

Many young Ugandans refer to the president by the nickname “Sevo”, and he fondly calls them Bazukulu (meaning grandchildren in the Luganda language).

But the family man does not see himself as a typical ageing patriarch, reclining in his favourite chair with his children and grandchildren fussing around.

In his campaign for his sixth elected term in office, which feels like it started straight after the last election, he has been traversing the country, launching factories, opening roads and new markets.

And with an eye on his relatively youthful challenger, 38-year-old former pop star Bobi Wine, Mr Museveni has been keen to show his vitality. Last April, to encourage exercise during lockdown he was filmed doing press-ups, and then repeated the trick several times including in front of cheering students in November.

After work last night, I challenged my Bazukulu to an indoor work-out. We did Forty Push-ups.

Just like I have always advised, even at your own home, you can stay safe, and remain fit and healthy. pic.twitter.com/LKjqwViwlE

— Yoweri K Museveni (@KagutaMuseveni) August 5, 2020

“If your father loves you, he has to empower you. In the next five years, ‘Sevo’ will make sure that when we finish school, we are able to get jobs,” 25-year-old Angela Kirabo says, touching on the issue of youth unemployment, which is a major source of concern.

The economics graduate is a proud Muzukulu (grandchild), having grown up in a family supporting the governing National Resistance Movement (NRM). She also served as vice-chairperson of the party’s chapter at university and thinks the president still has a lot to offer after 35 years in power.

Presidential age limits overturned

One of his closest friends and advisors, John Nagenda, says Mr Museveni’s selflessness is one reason for his ability to inspire loyalty.

“He was prepared to die for Uganda. I would say that we are very lucky to have him,” the 82-year-old says.

“Most of the other people that I know who have been presidents, they wanted to do it for themselves; they wanted the glory. But Museveni wants to do [it] for the country and continent… he is an Africanist.”

Nevertheless under the original clauses of the 1995 constitution the president should not have run for office again after 2005.

Indeed, before then it was widely understood that he was against staying on in power, brushing off queries about the idea, saying that he would rather go back to his farm.

Journalist William Pike, who at one time was seen as very close to the president and the NRA, described in his memoir how the president was genuinely upset when asked at a dinner in the early 1990s whether he wanted to stay in power for the rest of his life.

“Museveni said: ‘Of course not’, but he was clearly furious at what he considered a real insult. He was not faking it. At that stage he really was not intending to stay on in power,” Mr Pike wrote.

But something changed his mind in 2004, though it has never been clear what exactly that was, and his MPs endorsed the idea that the constitution should be amended to remove presidential term limits.

He had the green light to stand until he reached 75 years of age.

And then in December 2017, the constitutional obstacle of an age limit for a presidential candidate was also removed – an issue which led to brawls on the floor of parliament and a police raid on the building.

Many saw this as the NRM’s way to allow Mr Museveni to become president for life.

It is not for nothing that parliament felt compelled to reward the long-serving leader. The willingness of MPs to go along with the changes has a lot to do with the fact that they felt they owed their positions to the president.

Fewer challenges to authority

The significance of patronage extends right through society.

It sometimes manifests as development programmes for women, market vendors and government jobs. In a country where 15% of young people are unemployed and over 21% of the population live in poverty, aligning with the right party can save an entire village from destitution.

But his supporters point to the transformation of Uganda as a positive reason to give Mr Museveni five more years.

“If you come from the north and east you will understand that a big achievement of peace has been brought. For 20 years those regions were engulfed in war,” says 28-year-old Jacob Eyeru, who leads the government’s National Youth Council.

While acknowledging that joblessness is a worry, he adds that the NRM has “transformed the economy to make it not just regionally competitive but also globally competitive”.

Despite these changes he has also weakened the independence of some of the country’s key institutions to ensure fewer challenges to his authority.

The judiciary has not been spared, and in recent years has been accused of recruiting so-called “cadre judges”, who are loyal to the government.

When judges have taken independent decisions, they have sometimes found themselves at loggerheads with the authorities.

For example, on 16 December 2005, highly trained armed security personnel raided the High Court in the capital, Kampala, and re-arrested members of the suspected rebel People’s Redemption Army, who had just been acquitted of treason charges.

“They turned the Temple of Serenity into a theatre of war,” Justice James Ogoola wrote in a poem about the incident entitled Rape of the Temple.

When it comes to challenging election results, the outcome of every presidential race since 2001 has been contested in court. In all cases, the courts ruled that the irregularities were not serious enough to warrant an annulment.

The media has also had its independence threatened.

On the surface, Uganda has a lively media industry which has grown to hundreds of private radio and TV stations, print outlets, and internet-based services under Mr Museveni.

“In the early days, before cynicism and rot set in, there was a strand of intellectualism within the regime that tolerated dissenting views and was able to debate and disagree with them,” says Daniel Kalinaki, the Nation Media Group’s General Manager for Editorial, in Kampala.

But outlets have been raided and journalists detained, as the leading lights in the government have become “increasingly thin-skinned”, Mr Kalinaki adds.

But perhaps the most significant factor in Mr Museveni’s longevity is the way that any potential opposition force has been neutered.

Opposition supporters shot dead

As it became clear 20 years ago that he was going to stay in power, some of his former associates started to break away. As they did, the security forces, touted as a people’s police and army, turned their guns on these political opponents.

Kizza Besigye of the opposition Forum for Democratic Change, once Mr Museveni’s physician, first ran against him in the 2001 election. He has been detained and prosecuted on numerous charges, including rape and treason, but has never been convicted.

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGESNow that Bobi Wine, a singer whose real name is Robert Kyagulanyi, is mounting a serious challenge to the president’s rule, he has become the latest politician to face the wrath of the men in uniform.

The MP, whose star power draws huge crowds of young people, was brutally arrested during a colleague’s by-election campaign in the north-western town of Arua in 2018. He then faced treason charges which were later dropped.

On the campaign trail for this election, the police have arrested, tear-gassed and shot at him and his supporters for defying coronavirus restrictions on the gathering of large groups.

During two days of protests in November following Bobi Wine’s arrest, 54 people were killed, many of them believed to have been shot by the security forces.

Sticking your head above the parapet in Uganda is a brave choice and anyone who seeks to challenge Mr Museveni should be in no doubt about the level of harassment that they are likely to face.

Through his 35 years in charge, he has come to sit at the apex of power where he is in total control. He has also managed to reinvent himself.

Whereas he was once the political upstart in his early 40s, anyone taking on that role now risks incurring his considerable wrath.

BBC