After the nightmare of the Second World War, the economies of Western Europe were on their knees. And so, on 3rd April, 1948, the United States launched an economic recovery program unprecedented in its ambition. Over the next four years, the U.S. would extend a strong hand and lift these crippled nations out of the ruins of the world economy. It would transfer over $12 billion—around $128 billion in today’s money—and remove barriers to trade, modernize industries, and increase prosperity. The GDPs of the Western European countries rose by up to 25 percent, and their vital industries underwent rapid renewal.

This was the Marshall Plan. And it takes on fresh relevance today, as the world’s economies buckle under the strain of the COVID-19 pandemic. But it takes on special significance for Africa, as it did even before the outbreak of the virus. Here, on the world’s fastest-growing continent, the exploding youth population can be given its chance to reach its potential and drive continent-wide—and indeed worldwide—change. And this is why, in 2017, I called for a tailored “Marshall Plan for Africa.” It was modeled on the European Recovery Program of 1948, but with the empowerment of African youth at its heart.

Make no mistake: Africa is not immune to the damage wrought by the coronavirus. In my native Ghana, more than 6,000 people have contracted COVID-19. Abebe Aemro Selassie, director of the International Monetary Fund’s Africa department, has warned that the continent’s economy will contract by 1.5 percentage points this year. That is a loss of some £163.5 billion for the countries of Africa.

The pandemic, then, is a real and far-reaching humanitarian and economic challenge from which no country can hide. That cannot be overstated; not should the suffering it has caused around the world be overlooked. It also represents an opportunity to make an ambitious and workable Marshall Plan for Africa a reality. This must be engineered by the African Union, which has the presence and reach to direct a plan of this scope. But it can, and should, involve the entire international community.

Here, in the strangest of circumstances, there is a chance for meaningful global investment to end poverty, improve health infrastructure and introduce inclusive education. There is an opportunity to end the “give and take” development cooperation model that has predominated since the 1960s, and build up an Africa that is not isolationist, but can stand on its own two feet, trade with the world, create jobs for its people, and come up with its own solutions to its own challenges. The benefits of this will be felt far beyond its shores.

The foundations we need

What Africa does not need is more foreign aid. The large parachute aid payments that began in the post-independence era have come in many forms, from the social to the humanitarian, but all of them with strings attached. This kind of aid has helped to fight illness, provide clean water and bring teachers to the undereducated. But it has been effective only insofar as it has lessened immediate suffering. It has not given the countries of Africa the foundations they need to develop sustainably themselves.

Despite the internationalist and moral convictions that lie behind these foreign aid packages, they have trapped Africa within a vicious cycle. Each fresh injection of aid condemns the continent to more debt repayments and brain-drain. It is because of this that waves of economic refugees have left their countries of origin in search of better opportunities, denying those countries their best minds and animating rising nationalism and anti-immigration sentiment in Europe and elsewhere.

Sustainable development can only come about through intelligent investment in infrastructure, in enterprise, in energy, and in ideas. And the continent is showing its enterprise in the form of rising innovation, reflected in the firms of Silicon Savannah, the startups of Lagos’s Yaba district and in companies like Jumia, which became the first African startup to list on the NYSE last year. Aid does not build strong societies. That comes from the ingenuity of those within those societies—so long as they are given the opportunities to show their creativity and enterprise.

A Marshall Plan for Africa, directed and coordinated from within Africa, through cooperation and communication between its member states, can modernize and industrialize the continent. It can provide the recovering economies of Europe and elsewhere with access to 1.2 billion consumers, and give Africa the chance to renegotiate its relationship with the rest of the world, from one long based on debt and aid to one that rests on trade, investment and sustainable development. From Cape Agulhas to Ras Ben Sakka, and from Cape Guardafui to Santo Antao, Africa is increasingly showing its potential, and there is growing and justified confidence that our natural resources and human capital can become the foundations of strong economies continent-wide.

No single African state can drive this change by itself. Only the African Union, fundamentally a unifying body, has the infrastructure to push a narrative of deeper integration and call loudly on the world to transform this idea, of a Marshall Plan for Africa, into a reality. As the continent’s economies shrink, we must not panic. Instead, we must see the opportunity that has presented itself to us. It is a rare one. Here is a rare chance to empower the world’s youngest and most dynamic region to the benefit of all.

We must remember that the great lesson of the Marshall Plan of 1948 has nothing to do with the size of the aid package given. It has everything to do with the credible commitment that lay behind it. All sides agreed to have as their shared goal sustainable development, financial independence and peaceful, prosperous relationships. It was in the interests of all the countries involved that that became a reality. This is what I envision for a Marshall Plan for Africa. And, in the long run, it is also a Marshall Plan for the world.

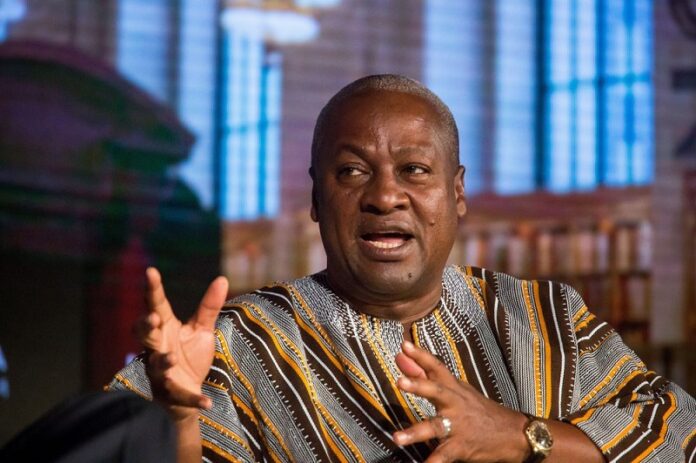

John Mahama is the former President of Ghana (2012-2017).

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own.

Columnist : J.D Mahama