Among the Luhya community in western Kenya, a tradition of bull-fighting exists. Originally practised to mark important events such as funerals, the sport has evolved into a more competitive and at times profitable pursuit.

Photographer Duncan Moore travelled to see how community leaders in Kakamega county want to bring it into the mainstream, forming leagues and working to have it recognised as a legitimate sport.

Image copyrightDUNCAN MOORE

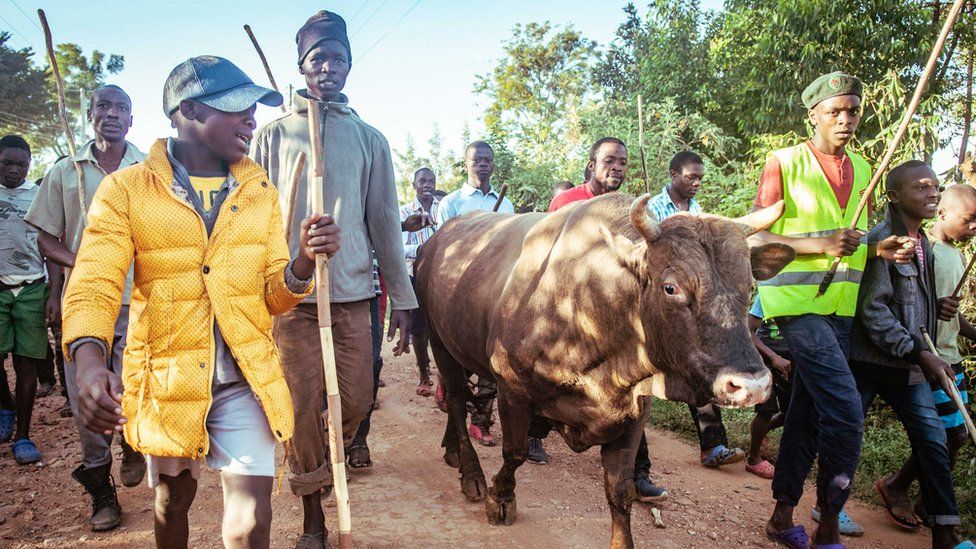

Image copyrightDUNCAN MOOREEarly Saturday morning and a bull-fighter and his entourage make their way to the designated fighting ground where he will pit his bull against an opponent from another village.

Image copyrightDUNCAN MOORE

Image copyrightDUNCAN MOOREThe procession features Isukuti musicians, who play a traditional form of music from western Kenya and accompany the bull as it makes its way to the fight, attracting more people along the way.

Image copyrightDUNCAN MOORE

Image copyrightDUNCAN MOOREAs the crowd grows, kids climb trees both to get a better view and to avoid the bulls on the ground. While this is a smaller, local match up, major events at designated venues attract huge numbers of people.

Image copyrightDUNCAN MOORE

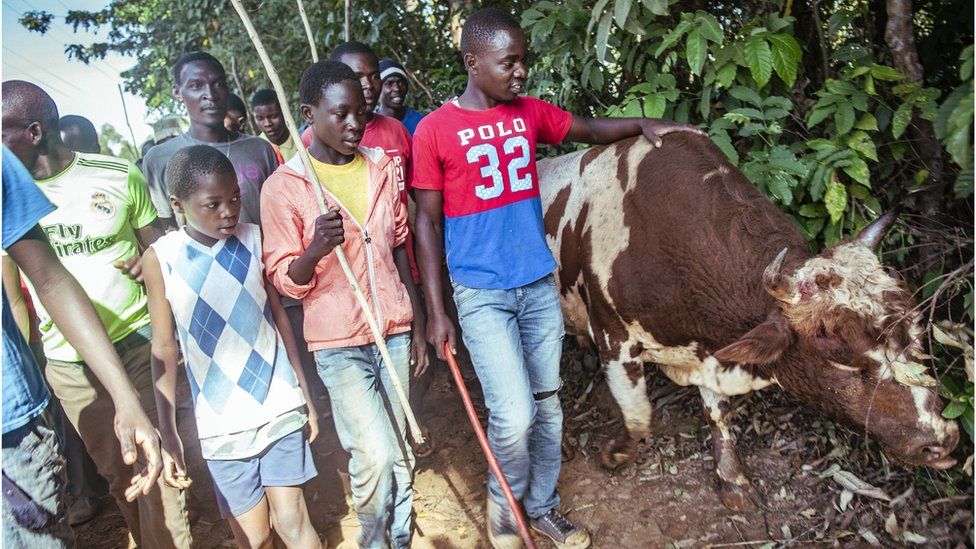

Image copyrightDUNCAN MOORESpectators examine one of the bulls, Misango, before the fight. Still young with the potential to grow, a bull like this could sell for 80,000 Kenyan shillings ($800; £633). The most expensive bull ever sold, a champion fighter named Nasa, fetched 260,000 shillings.

Image copyrightDUNCAN MOORE

Image copyrightDUNCAN MOOREThe other competitor, Tupa Tupa, charges at one of the men trying to escort him to the fight. Groups of men with sticks do their best to corral the animals, but when a bull decides to run there’s not much anyone can do.

Image copyrightDUNCAN MOORE

Image copyrightDUNCAN MOOREArguably the most dangerous part of the sport, especially in informal events such as this, is watching it. Here a girl is carried away after being knocked over by a bull that decided to flee instead of fight.

Image copyrightDUNCAN MOORE

Image copyrightDUNCAN MOOREAfter sizing each other up for several minutes the bulls launch into each other and the fight is on. While they can be herded towards a certain area, the animals fight where they want to, which in this case happened to be a maize field.

Image copyrightDUNCAN MOORE

Image copyrightDUNCAN MOOREKakamega bull-fighting is an up close and personal experience, with the crowd following the action and running occasionally to avoid getting hit.

Image copyrightDUNCAN MOORE

Image copyrightDUNCAN MOOREParticipants and spectators circle the competitors and cheer on their preferred animal, creating an atmosphere more akin to a fight club.

Despite objections from some animal rights activists, proponents of the sport say it is an important economic activity and part of the Luhya cultural heritage.

Image copyrightDUNCAN MOORE

Image copyrightDUNCAN MOOREGerald Ashiono, chairman of the local Bull Owners Welfare group, also looks on. The association works to ensure fights are registered, bulls are taken care of and proper arenas are found.

Image copyrightDUNCAN MOORE

Image copyrightDUNCAN MOOREHorns locked, Misango (left) and Tupa Tupa (right) battle for dominance. Mr Ashiono says that bull-fighting is an intangible part of the region’s heritage, spanning generations: “My grandfather owned bulls, my father owned bulls, now I own a bull.”

Image copyrightDUNCAN MOORE

Image copyrightDUNCAN MOOREA fight breaks out between two men representing different bulls. With gambling on the outcome a major component of the sport, tensions can run high during fights.

Image copyrightDUNCAN MOORE

Image copyrightDUNCAN MOOREThe crowd cheers as the bulls move from the maize field towards another farm.

According to Mr Ashiono this form of bull-fighting is more humane than the Spanish variety: “The bull has a choice, if it doesn’t want to fight that day you can’t force it.”

Image copyrightDUNCAN MOORE

Image copyrightDUNCAN MOOREDefeated, Tupa Tupa and his owner return home. While unsuccessful bulls may eventually be sold for meat, a key difference with Kenyan bull-fighting is that no bulls are killed in the process.

Image copyrightDUNCAN MOORE

Image copyrightDUNCAN MOOREMisango, the victor after forcing Tupa Tupa to run away, is escorted back to the owner’s village by a crowd of jubilant supporters.

Image copyrightDUNCAN MOORE

Image copyrightDUNCAN MOORERaising a fighting bull is not easy. The animals are pampered and fed a specific diet featuring supplements and local herbs.

Mr Ashiono, pictured here with his prize bull Imbongo, says: “For us, it is a cultural event, a community event and also a sport with a huge following. The future of bull-fighting is very bright.”

BBC

Photos by Duncan Moore